UAE investors ponder the spectre of deflation

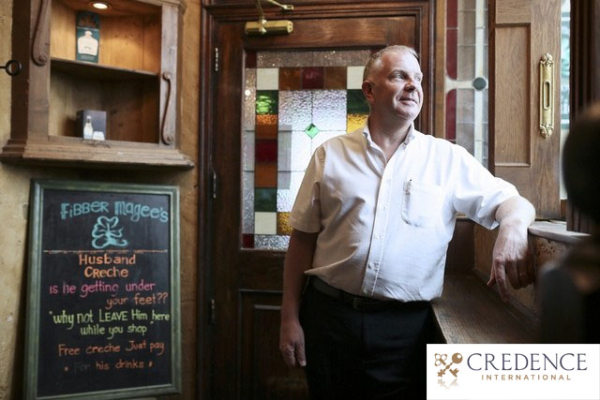

To make money, you have to take a few risks. That’s the view of Mark Hutton, a British businessman living in Dubai.

Accepting a little risk is particularly important in today’s low inflation world, where simply leaving money in cash merely guarantees you a near-zero return.

But you have to keep your nerve, especially as the major western economies and emerging markets are increasingly menaced by deflation, as prices fall in real terms year-on-year.

Mr Hutton, 54, the founder of the Irish pub Fibber Magee’s, says that as an investor he has always been “bullish by nature”, adding: “I have always been prepared to take risk to achieve growth.”

He isn’t too worried about talk that stock markets may be overvalued or that deflation may hit future growth expectations.

“After being in the financial markets for many years I understand that volatility to a certain extent can mean opportunity and if I am investing money I want it to grow,” says Mr Hutton, who has lived in the UAE for 21 years.

But with a wife and three young daughters aged nine, five and two, he is slowly becoming less adventurous. “I have always diversified my portfolio between different securities and asset classes, and also different advisory firms and financial institutions.”

Mr Hutton, who is taking advice from the Dubai-based wealth advisers Credence International to help spread his investment risk, founded Fibber Magee’s in 2004 and says business has held firm during recent swings in economic fortunes. “I haven’t been too affected by the economic slowdown. I have some very loyal customers and the big events in the region that I cater for continue to produce good numbers year on year.”

Expats may be feeling bullish in the UAE, where another construction boom is under way, but confidence isn’t as high in the rest of the world,which has a new worry on its mind: deflation.

While inflation in the UAE rose 4.3 per cent in the year to March 2015, prices have been worryingly flat or even falling in the US, Europe and some major emerging markets. Many see this as a sign that their economies are going into full-blown retreat – a concern for UAE expats with pensions and savings in countries such as the US, UK and Europe, and emerging market giants such as China.

In the US, prices for goods actually declined 0.1 per cent in the year to March, according to the labour department. That means it actually cost less to buy things in America than in March 2014.

The euro zone fell into deflation in January, with prices down 0.6 per cent year-on-year, and they were still falling in March, down 0.1 per cent. Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Greece and Portugal have all experienced price falls.

UK inflation fell to zero in February and April’s figures could result in it turning negative, while the People’s Bank of China warned in March that its once- rampant economy was slipping towards deflation.

The tumbling oil price is partly to blame, and food costs have fallen as well. Another issue is low wage inflation, as workers in the West struggle for growth in their pay cheques.

Demographics are a long-term worry, as ageing western populations face an uphill battle to outgrow rising healthcare costs.

Deflation is particularly fearful given that the global economy has yet to reach escape velocity after the financial crisis, and central bankers have used up almost all their fiscal and monetary ammunition.

Chris Ferguson, the chief executive of Credence International, says that while deflation sounds appealing in theory, it can be devastating in practice. “Deflation happens when the price of goods and services falls, so things are getting cheaper. The danger is that consumers delay their spending, because items may be even cheaper next week, or the week after.”

This can lead to a negative spiral as sales drop, profits fall, factories close, workers are laid off, incomes deteriorate, companies and consumers default on their loans, which leads to a further drop in sales, Mr Ferguson says.

James Thomas, managing director at the independent financial advisers Acuma in Dubai, says that stock markets can quickly get sucked into the deflationary vortex.

“Just look at what happened in Japan. When it fell into a deflationary cycle the Nikkei 225 plunged from its record high of 38,580 in December 1989 to less than 8,000 some 15 years later.”

Investors still have not recouped their losses, with the index still trading below 20,000, roughly half its peak more than 25 years ago.

Japan has now suffered two “lost decades” despite near-zero interest rates, and many fear the West could be following its lead.

David Norton, head of investments at AES International, says the signs of deflation are all around us and investors should be worried. “Sustained deflation is devastating for investors. The Great Depression in the US in the 1930s and Japan’s two lost decades killed stock markets in those countries.”

On paper, however, savers gain. “Their money is worth more, because even the smallest amount of capital growth boosts their buying power at a time when prices overall are falling,” says Mr Norton.

The downside for savers is that central bankers will not hike interest rates while prices are falling. Analysts expected the US Federal Reserve to increase interest rates in the summer, but now the expectation has been deferred to September at the earliest, while Citigroup doesn’t expect the first rise until December. The wait could be even longer than that.

Any UK rate hike has been put back to 2016 at the earliest. In Europe, rates are expected to stay at today’s levels for several more years, as the ECB battles to haul inflation back up to its 2 per cent target. Countries such as Sweden, Denmark and Switzerland now have negative interest rates, which means you actually pay the bank to hold your money.

So what should investors do about it?

Mr Norton says: “Although the economic rules may have changed, the investment rules haven’t. The best way to protect yourself is through careful asset allocation, which means spreading your money between shares, bonds, cash, property and other assets.

“You need to assess your portfolio and make sure you have still got the balance right.”

He adds that although the property and stock markets are the most vulnerable to deflationary pressures, there are exceptions. “If you are buying individual stocks, you should look for high quality, defensive companies with the size to retain pricing power, which means they can raise their prices without losing customers. Also, look for stocks paying regular dividends, as they should give you far higher income than cash.”

Tom Stevenson, investment director at Fidelity Personal Investing, says there can be winners in the short term, especially where deflation has been driven by falling oil prices. “Airlines have enjoyed a massive windfall from energy-led deflation in the form of cheaper oil.”

Bonds offer investors a fixed income that will seem increasingly attractive in an environment of falling prices, he adds: “Cash, too, looks like a safe haven if its purchasing power is increasing.”

After a six-year bull run, Mr Ferguson warns that many investors may be exposed to too much risk. “You need to review your underlying portfolio and see whether it reflects your attitude to risk. Risk assets are fantastic in good times but markets drop quicker than they rise and a decline in valuations is a lot harder to come to terms with than a gain.”

An economic whirlwind

The big question is whether deflation is a passing phase, or set to worsen. Disappointing first quarter GDP growth figures in both the US and UK suggest both economies are losing speed.

In Japan, the prime minister Shinzo Abe is endeavouring to turn the deflationary tide with his three-pronged “Abenomics” plan, a combination of fiscal expansion, monetary easing and structural reform that looks like a last throw of the dice for this once-booming country.

And in the euro zone, the European Central Bank president Mario Draghi has unleashed €1 trillion (Dh4.12tn) of quantitative easing; again, in a belated bid to drag the continent out of its deflationary malaise.

There are early signs that this is having an impact, notably in Europe, but David Norton, head of investments at AES International, says the biggest worry is now China, where the authorities face a desperate battle to gently deflate the country’s credit and property bubble.

As the world’s second-largest economy, China is in a position to export its deflation throughout the world, which has driven the fall in commodity prices.